Sinking House

Longlisted

Activism

Archiboo Awards 2022

Shortlisted

Sustainable Project of the Year

Insider South West Property Awards 2022

Shortlisted

Installation Design

Dezeen Awards 2022

Winner

Collaboration of the Year

AJ100 Awards 2022

We are at a tipping point.

The time to act on the climate emergency is now, before it’s too late.

Sinking House is a message of warning, and hope, to communities across the world – including leaders gathering at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) – to address the issues, reach for lifelines and act now against the intensifying threat of climate change.

The warnings are all around us.

Climate change is being accelerated by our actions.

Hope for the future requires positive action.

We can take inspiration from community action. Be that from global leaders or grass roots movements. COP26 should be a lifeline to all of us as we face potentially devastating changes to the way we live.

The installation

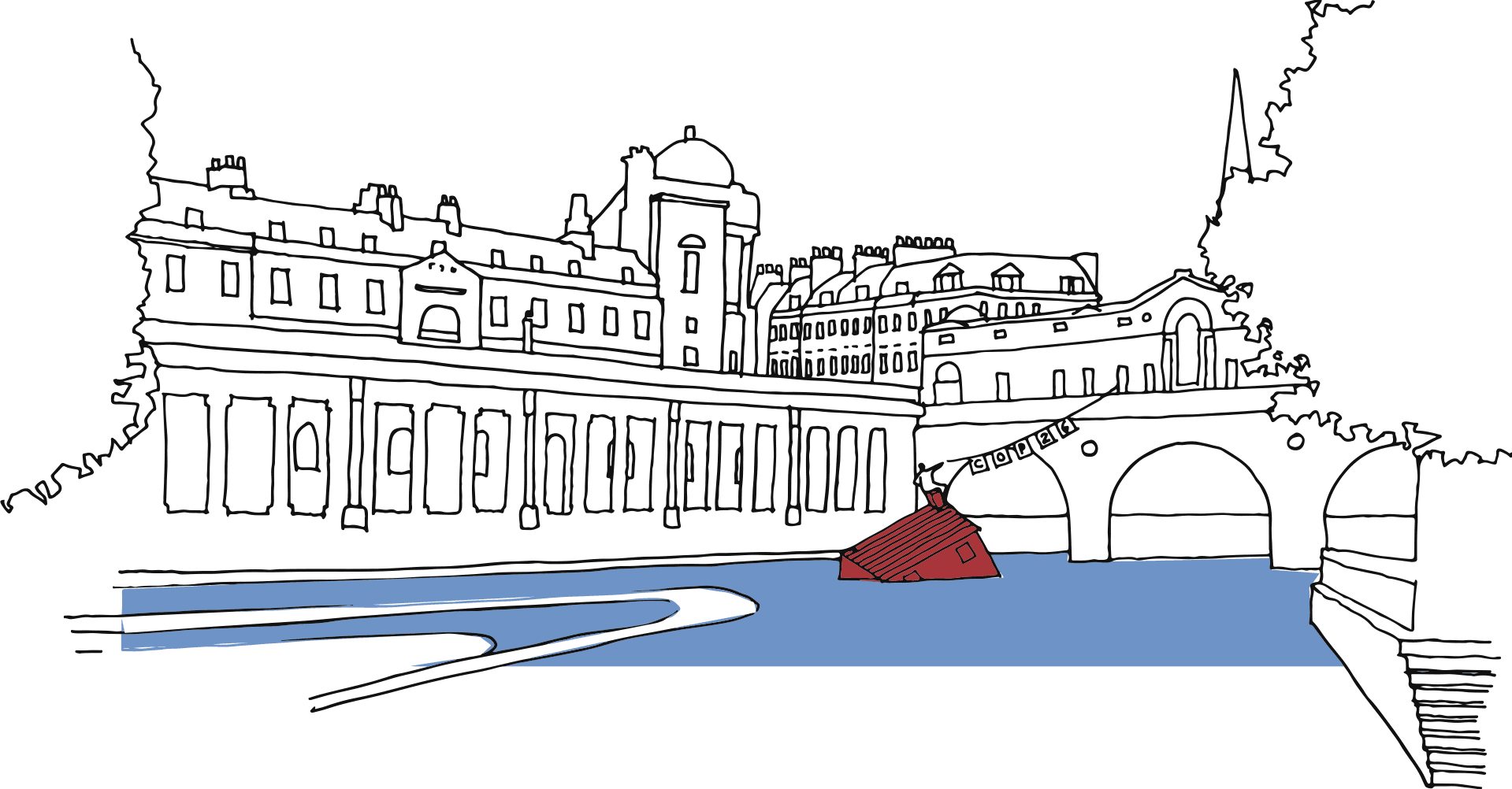

Placed in one of the most iconic locations in Bath, Sinking House appeared semi-submerged and at a tipping point between Pulteney Weir and Pulteney Bridge. On the chimney, a human-like figure held a lifeline which reads ‘COP26’.

Located in a seemingly perilous location just above the turbulent weir the house’s vulnerability and that of the figure on top represents the dangerous position we have put ourselves in today with climate change. The piece highlights the need for immediate action to avoid devastating consequences.

The built environment

Sinking House coincided with the closing of our Climate Action Relay, an 8 week programme to provoke and inspire collaborative action across the built environment, and we hope Sinking House does the same.

We can’t escape the fact that the built environment is a major contributor to global CO2 emissions. But we can agree that more can be done by those who shape this industry to join forces to reduce our negative impact on people and planet.

Head over to Twitter and follow the latest from #SinkingHouseBath

Making it happen

Sinking House was led by Stride Treglown and Format Engineers, with artist Anna Gillespie and Fifield Moss Carpentry.

We worked with local tradespeople to help build the sculpture. This helped to minimise transport emissions and keep the installation as sustainable as possible.

It took an entire community of local people and organisations to make happen. Special thanks goes to Bath and North East Somerset Council, The Environment Agency, City of Bath Sea Cadets, Greenman Environmental Management, Bridge Coffee Shop, Sydenhams, Kellaway Building Supplies, Minuteman Press, RIBA, Wessex Water, Architecture Is.

Meet the makers

Rob Delius

Rob Delius is an architect and Head of Sustainability at Stride Treglown. The idea for Sinking House started with him.

Let’s start at the beginning, where did the idea for Sinking House come from?

The idea actually came out of Stride Treglown’s Climate Action Relay which was a programme of events, counting down to COP26, focused on the climate emergency. Over eight weeks, we wanted to host discussion events but we also wanted to have ‘doing’ events. So I was thinking about what we could do in Bath which would have real impact.

I did some sketches of an installation and I contacted Format. They’ve done amazing work and incredible art installations all around the world and they’re based in Bath, so I thought it would be fantastic to work with them on this project. And to my absolute joy they said ‘Yes, count us in’.

So we had a few initial conversations about what we could do. We were first looking to do something in the park but then a colleague in our Bristol office suggested that we do something on the water. I thought actually that’s a good idea – pretty ambitious – but it would have huge impact. And that’s what we wanted for this project: for as many people to see it, to talk about it, and to share it. It’s all about spreading a message about the climate emergency and spreading the message about COP26 being a make or break moment.

And turning the idea into a reality – how was that process?

It’s been pretty up and down. I won’t lie about it. We’ve had quite a few challenges but we’ve got an amazing team working on it who’ve got a real can do attitude – so we’ve managed to find a solution to everything that’s been thrown at us. And we’ve had amazing support from so many local people and organisations in Bath – it’s been a real community effort.

Why do you think this installation, and its message, is so important?

I think climate change, net zero and sustainability – these topics are all so big in the construction industry now. I think everyone’s so much more clued up than they were a few years ago. But I think there’s still a lot more awareness that we can share generally. Some of the details about what’s happening to our planet are really quite frightening. We are at a tipping point now. This is an emergency. I feel our mission with this project is to get that message across to people.

How do you think people in Bath are going to respond to the installation?

Everyone that we’ve spoken to so far – from local organisations to people in cafes – thinks it’s fantastic idea. So I’m really hoping that the public will be excited by it too. I hope they’ll get the message and get behind our call for climate action.

Have you done anything like this before?

I’ve been involved with quite a few initiatives at Stride Treglown, mostly all aimed at the construction industry. This time, it’s really exciting to be doing something which is connecting to people who aren’t just within our industry – it’s much bigger than that. Everyone is going to see this and so it feels like we can make a difference and have an real impact on people.

It’s great that Stride Treglown supports people to do projects like this which are outside of the norm or not part of the usual day job. They recognise the influence that something like his can have and they can see how this can be a really beneficial project for the local community and beyond.

Do you have any personal takeaways from this project?

For me, this installation is more art than architecture. I think there are really interesting connections between the two and we [architects] should be exploring how our work could embrace art more as a means of communication. I believe we should be pushing boundaries, in terms of creating things which are beautiful or have a powerful message, to connect to people in a different way than say a building does.

Finally, how will you know if Sinking House has been a success?

For me, I think it’ll be successful if I can sense that a lot of people are seeing it, they’re interacting with it, they’re getting the message and they’re sharing it. I’d love to see that ripple effect of people saying ‘Go and see this thing in Bath’.

Sarah Perry

Sarah is an architect who, until very recently, worked at Stride Treglown. She created the initial drawings and 3D model for Sinking House as well as handling the planning applications.

Hi Sarah, can you tell me about your role in the project?

So I was involved from the beginning. Originally, I was creating the 3D model of the house design and then doing the drawings and the applications and various bits. Towards the end, I actually said goodbye to Stride Treglown but I was keen to continue working on the project and see the installation through to the end.

What motivated you to continue with the project?

It’s such a unique project with a really important message. When talking to people about the installation initially, it became clear that many didn’t even know what COP26 was. We have a climate emergency and it’s really important that people understand there are events like COP26 happening. I hope the installation creates some awareness.

What have the challenges been?

Where do you start? It’s like one step forward, one step back. We’d progress in one area, for instance our Environmental Agency application, and then we’d find we’ve got difficulties finding somebody to install it in the river. So there’s been a lot of backward and forward.

Have you worked on anything like this before?

No, this is probably the most unique project I’ve worked on and the most community involved project. Originally, it started out with quite a small group of people. It was Stride Treglown and Format and that’s kind of exponentially grown. Now, when you look at the display board, we’ve got a whole list of people that have contributed and a lot of people have put their time in for free, myself included. It just makes it feel really worthwhile.

How do you think the Bath public will respond to the installation?

In the same way the public responds to anything, I guess. Some people will like it, some people won’t, some people won’t understand it. Hopefully, it’ll be positive overall. If nothing else, it should raise awareness of the climate emergency and get people thinking – that’s the main thing.

What are your takeaways from the project?

For me personally, this project has made me realise that I want to focus more on sustainability within architecture going forward.

Lloyd Evans

Lloyd is a Chartered Structural Engineer at Format. He straddled the divide between design and build and is the reason Sinking House floats!

Hi Lloyd. So, how did you get involved with Sinking House?

We’re based in an office literally just across the river. Stride Treglown approached us a few months ago wanting do something for the COP26. We threw a few ideas back and forth and landed on a Sinking House in the river. It felt like a bit of a long shot at that point with lots of bureaucratic hoops to jump through in terms of permissions from the Environment Agency and the Council – but we did it!

And how about the design and build, was that more straightforward?

Well, the timber frame itself is quite conventional (until you tip it on its side and make it look like it’s sinking) but it’s not often you have to design something that’s floats, something that’s buoyant. That added an extra dimension to the project which made it interesting and quite fun.

What was your role on the project?

I ended up somehow straddling the divide between design and build. One week I was doing the drawings and then the next week I was helping on site. Just from a personal point of view, it’s been really good because it’s not often you get to go from one side of the desk to the other. It makes you realise that the stuff you put down on paper has some serious consequences to the people who have to put your ideas into action on site.

What motivated you to get involved?

I was quite excited by the idea of doing something quite visual. It had a bit of a ‘guerrilla installation’ vibe about it. It’s quite a stark intervention in a city that’s generally quite sleepy and quiet. The idea of doing something that was quite eye-catching for such a worthy cause – or an emergency situation should I say – was really appealing.

It’s nice to do a project that’s so local as well. We’re in an office that overlooks the river and we’re doing an installation straight onto it and with other local organisations too. It’s been a real coming together of different local contacts and friends. I’ve known Sam, the carpenter, since I was at Bath University. So when we were looking for somebody to build Sinking House, he was one of the first people that came to mind because he’s local and doesn’t get phased by unusual projects.

It’s been great. I don’t think we ever would have ended up having any dealings with the Sea Cadets, for instance, unless we were doing this project. And we hadn’t worked with Stride Treglown before so that was nice. Then before you know it, you’re calling around and all these people are getting involved and it’s a real sense of community with everyone working as a team.

How do you think it’s going to be received in Bath?

Bath is a relatively liberal city and so I think it’ll be received well. But I’m hoping that it will reach a wider audience too. I’m hoping that it’ll have enough visual impact that people will want to go there and take photos of it and then the message about climate action will spread even wider.

Is sustainability and climate action something you feel passionate about?

The more I read about climate change and the more we talk about low carbon design in work, the more I feel personally responsible. For me, the construction industry still has a lot to do. It’s all been baby steps so far.

As an engineer who designs things every single day, I think we’ve got this opportunity to leverage a huge amount of change. A few months ago the Institute of Structural Engineers had an article which did a simple material comparison. It stated that if the average engineer swapped out every small steel beam for a slightly bigger timber one over the course of their career, it would lead to an embodied carbon reduction that far outweighs the carbon most individuals will produce in a lifetime. That really hit home and since then I’ve upped my game.

We, in the construction industry, now have choices to make. Our decisions – big and small – can make a massive difference.

Anna Gillespie

Anna is an artist, sculptor and climate activist based in Bath. She created the human figure which sat on top of Sinking House.

Hi Anna. Can you start by telling us how you first got involved with Sinking House?

So I got a phone call from Funda Kemal who I met through Extinction Rebellion (XR). She put me in touch with the architects, Rob Delius and Sarah Perry. They explained the plan and said ‘Are you up for it?’ and I just instantly thought yes, of course I’m up for it. I felt this was a really good opportunity for me to use my skills and make a contribution.

What was it about the project that interested you most?

Ironically, just over a year ago, I installed three banners with XR across Pulteney Bridge saying ‘We’re Up Sh*t Creek’. That was such a wonderful project. It was all completely covert and done without permission. And then suddenly I had an invitation to work in exactly the same place, this iconic location. But, this time, there were actual people and tourists around. Whereas my previous project with XR happened during lockdown and the city was completely dead.

Do you think your covert operation was as effective as an organised approach?

I think the organisation probably did count for something. Sinking House got into China Daily and all sorts of other press. But of course you can do something illegal, like XR did with their Pink Boat, and surprise everybody and that’s fabulous too. Honestly, I don’t think that question’s got one answer to it.

How do you think Sinking House compares to something like XR’s Pink Boat?

The boat was disruptive which the Sinking House sculpture wasn’t. Sinking House was a gentle gesture in comparison. There is something about disruption that captures people. As much as we fear not being liked – talk about Insulate Britain blocking motorways at the moment – the boat was transgressive.

Do you think Sinking House and its message potentially captured a slightly different audience though because of its less disruptive nature?

That’s interesting actually, you’re probably right. I think the world’s changed since the Pink Boat too; we’ve had the flooding events in Germany and the fires in Australia. I think when you get environmental disasters happening so close to home, it’s suddenly very shocking and people take notice. Those people on beaches in Australia – I hate to say this, but – they look like us, they’re wearing the same clothes as us, they’re driving the same cars as us. So it’s not as easy for people to distance themselves from what’s happening now.

I saw you posted a photo on your Instagram account of a person stood on the roof of a house surrounded by flood water. Was that the image that inspired Sinking House?

Yes. Rob Delius used the image on a mood board which is what got me interested in the project. Of course, I’d already seen those images. Obviously that person in the image is standing but practically it’s much harder to make a standing figure. You’d have to have a really solid armature braced inside the structure. By making a sitting figure, I knew that a very light armature structure would work.

So Rob came to my studio and we made it with a little bit of collaboration. I just kept showing him pictures and it was quite nice because it firmed up gradually over two weeks. Rob and Sarah actually posed for the sculpture which was great. Together, we worked out what the pose was and what the meaning of the pose was. It was all about trying to hold onto this lifeline but the head is turning towards jeopardy which was the flooding.

There’s been some discussion about the gender of the sculpture…

Yes, I’m really aware that it’s a male figure. This is a massive issue – it takes a bit of honesty to talk about. The male figure represents humanity. I think it was Simone de Beauvoir who wrote about the subordination of women and their categorisation as the Other… It’s why someone like Anthony Gormley – a 60-odd year old, white, non-disabled male – cast himself for his sculpture on Crosby Beach. He represents humanity. If you do a female figure, it just doesn’t. So as a sculptor what do you do?

It sounds like you’re bound by the language of art in some ways…

It’s the language of the entirety of our culture. Humanity is viewed through this patriarchal lens. If the figure was female, people would say, ‘Who is this? Why is it a woman?’. The way to represent humankind historically has been through the male figure and I went with that. It’s a communication piece and it was important that the main message wasn’t blurred by conversations around gender.

The other thing is that the average male is bigger than the average female so when you’re trying to create something that is both human-scale but has an impact from a distance, size is important.

That makes sense. So have you always been passionate about the environment? And does this passion manifest in your work?

So back in 2003, I started to feel really anxious about the climate. It sort of came upon me quite suddenly when we moved to Bath. I’d been doing things like sitting in the traffic on the London Road with my engine running just thinking we’re killing ourselves. It was as though a layer of skin peeled off and I could see the truth. I felt as though I was part of the problem.

So I went on this amazing course at the Schumacher College in Devon called Art in Place, with people like Anthony Gormley and Peter Randall-Page teaching, and I was able to express my anxiety. After being there for two weeks, I decided that I needed to let the art be of service. So for about eight years after I made sculptures out of found tree material, acorns and such. The work was a meditation on a rather deep green idea of humans and nature being at one.

Do you think your environmental work has made a difference to issues like climate change?

So I feel my personal work at that time was very beautiful but actually very limited in expression. It was considering the environment in a one-dimensional way – only looking at this sense of ‘oneness’. So I sort of moved away from it after a while because I thought this isn’t actually making a difference.

So when XR came into my life in April 2019, I jumped at it. And I’ve been able to use my art skills in a much more practical way which has felt an awful lot more effective than making art which is only seen in galleries. So I’m now helping XR with printing and banner making and I also have a visual eye on performance. It’s quite important to get the aesthetics right and a lot of activists don’t necessarily have practical art skills.

Would you say art in general is an effective form of communication though?

So my sister is a reasonably well known print maker. She makes mezzotints of moths and is using her art to talk about specific aspects of the environmental crisis, like the loss of insect biodiversity. She’s been featured in The Guardian and she does get an audience. So her art is doing something. And what’s more, she is not the kind of person who could go out on the streets and shout. Whereas when I’m on the streets it’s like I’m functioning at 110 percent.

And where do you think Sinking House sits within that thinking?

So interestingly, I consider Sinking House to be protest art. So similar to making a banner, it’s a visual communication piece. That to me is very different from the work you see around me in my studio which is more expressive.

Finally, do you think you learnt anything from the Sinking House project? Is there hope for the future?

Sinking House reinforced my existing feeling that I should take almost any opportunity to collaborate. When you see people collaborating, you think… yes, this is the kind of world we need to live in: a collaborative world, not a profit-driven world.

So where I’m living at the moment, we’re building a community and there’s quite a lot of talk about self-sufficiency in terms of things like food production. So for me personally, I’m making a constructive effort to seek and create sustainable ways to live. But I’m just not sure. People since the 60s, and even well before then, have been trying to work together to create alternatives. There’s a massive tradition where you try but I think real change will only come from political action.

Sam Fifield Moss

Sam is a carpenter at Fifield Moss Carpentry. He managed the Sinking House build with next level creativity and problem-solving skills.

Hi Sam. Can you tell us how you got involved with the Sinking House project?

I’m a carpenter and I’m also doing a degree in design specialising in the environment, which ties in very nicely with a project like this.

Lloyd, the project engineer, and I have known each other for a long time. He contacted me and told me about the project. He said it would be good to get a local carpentry team together rather than using one of the big contractors. And I was honoured to be asked and excited about it from the start.

What are the challenges when working on a project like this? What were your worries?

I would say no worries just problems that are yet to be solved! My background is doing builds for festivals across the UK, so I often find myself faced with an interesting concept, such as this. It requires a lot of thinking outside the box, working in different ways to how you might normally work with conventional carpentry and being very fluid with your problem solving.

What were your personal motivations for joining a project like this?

I’m passionate about the environment. I like to be engaging with what’s going on rather than worrying about it. It’s nice to feel like I’m helping to raise awareness of the climate emergency. Also, I love to build things. It’s nice to be involved with something interesting, creative and challenging.

You’re from Bath? Does that make this project more special to you?

Yes it does. I’ve lived in Bath my whole life so it’s great to be involved with something that will hopefully receive lots of attention within the city – and for such a good cause.

How do you think people in Bath are going to respond to the installation and its message?

I think Bath is quite an environmentally-aware city and I hope what this thing represents will be received well. It’s in a very iconic place, a highly photographed location. I’m excited to hear what people think.

End of Life

Sinking House was removed from the river after a two-week residency. The floating pontoon was gratefully returned to the City of Bath Sea Cadets. The house was carefully dismantled and the timber re-fashioned into an animal shelter on a small holding in Bath.