As part of the 2021 Festival of Higher Education, Stride Treglown hosted a webinar to discuss the results of an innovative sensory POE research project carried out at the University of the West of England’s (UWE) flagship Bristol Business School.

Cora Kwiatkowski, Stride Treglown’s Divisional Director, Sector Lead for Universities, and RIBA Client Adviser, chaired the event. Here’s her report.

The webinar panel

Matt Tarling, Stride Treglown’s Director for Universities, introduced participants to the Bristol Business School building (designed by Stride Treglown and completed in 2017). Professor Samantha Warren, Professor in Organisation Studies – University of Portsmouth, explained the research project.

They were joined by distinguished panel guests Dr Ghazwa Alwani-Starr, Pro Vice-Chancellor (Strategy, Planning and Partnerships) – University of London, and Professor Jane Harrington, Vice-Chancellor – University of Greenwich.

An introduction to the research project

Not surprisingly, providing the right type of space in university buildings is vitally important. Far from just an ongoing cost, it is the physical embodiment of the institution’s educational ambitions, philosophy, and brand values. User experiences of the building critically affect the university’s ability to attract the best students, and recruit and retain the best staff.

Unfortunately, traditional post-occupancy evaluations completely overlook these dimensions of design and so their results are not fully holistic. As a listening, people-centric practice committed to adding lasting value for our clients, this is frustrating and explains why we (along with ISG) were so keen to support UWE’s ‘sensory post-occupancy evaluation’ research project.

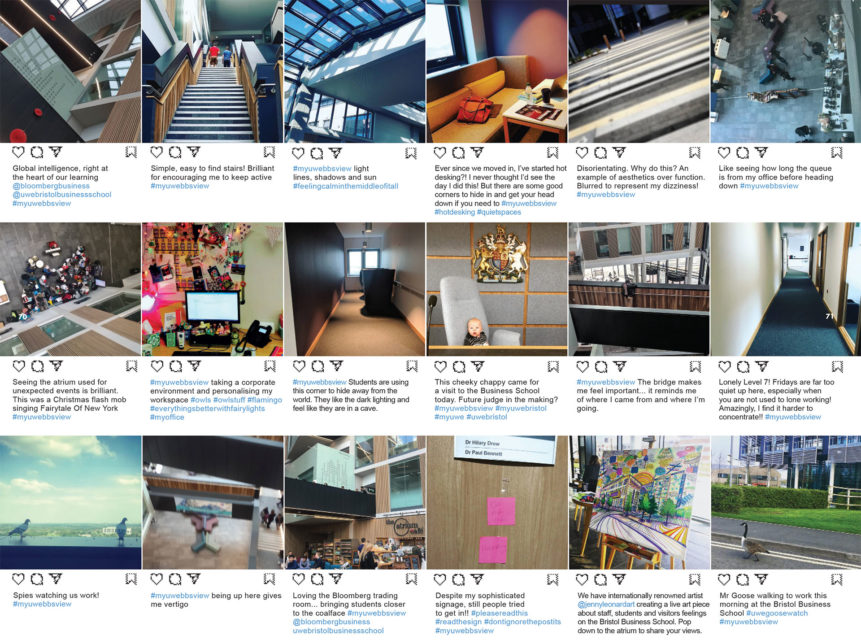

Running for a year from 2018 to 2019, this project led by Professor Samantha Warren and Dr Harriet Shortt, Associate Professor in Organisation Studies at UWE, dispensed with the usual survey format. Instead, it explored users’ emotional responses and lived experiences by inviting them to submit photographs (including through Instagram) of the building, along with a caption to explain why they’d done so.

As Samantha Warren explained, the novel methodology is, to the best of her knowledge, a first, allowing an analysis of users’ interaction with the building in fresh and nuanced ways.

We wanted to explore two of the most prominent findings in our webinar; the importance of active space management, and balancing privacy against openness in the design of university buildings.

Active space management

Matt Tarling pointed out that, despite the client brief for the building focusing strongly on the formal teaching facilities, these spaces did not appear in any of the photos submitted. Users’ focus of attention was entirely on the building’s informal, ‘deliberately ambiguous’ collaborative spaces, some of which didn’t seem to offer sufficient clarity of their intended use.

For example, some students reported being uncertain about whether teapoint spaces near staff offices were for their use, with the result that some left for the library instead. When they were colonised innocently by students, it caused so much tension among staff that the areas were subsequently reassigned as staff only.

This outcome was the opposite of the design intent, which was to maximize the building’s ‘stickiness’ and to bring staff and students closer together – an aim which was actually successfully achieved in other areas such as the welcoming atrium and cafe and collaboration areas.

It’s clear that users, while liking the building’s flexibility and ability to surprise, would welcome better demarcation of boundaries or rules of use, and that activities in spaces need ongoing management, perhaps by what Samantha Warren called ‘building custodians’.

This result fascinated Dr Ghazwa Alwani-Starr. With a vast experience of overseeing large capital building projects at the University of London, she knows that active space management is a key business priority:

When new and indeed existing space is unloved, it has a demoralising effect on staff and students alike. We must understand how space is used and respond to it.

She recognises the particular challenge of informal collaborative spaces because they are jointly owned and don’t fit neatly under any one budget. As she says, “They affect many areas of policy, straddling physical, social, cultural and financial boundaries.” She advocates the continuous review of the use and fitness-for-purpose of spaces not just through condition surveys but user consultation, too.

Professor Jane Harrington, now with the University of Greenwich, was previously Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Provost at UWE. Prior to this, Jane held the post of Pro Vice-Chancellor of the Faculty of Business and Law where she was instrumental in the brief and vision setting for Bristol Business School.

The project relocated staff who had been ensconced in unfit premises for decades. “Because staff knew they were headed somewhere better and were having lots of money spent on them, it inhibited criticism,” she recollects. At the same time, the University Governors, somewhat against the will of the staff, were pushing for a totally transparent, largely open-plan, overtly collaborative and outward-looking building.

These two factors probably made for a brief that contributed to the observations users subsequently highlighted during the sensory post-occupancy evaluation. As architects we are keen to engage in an open way with stakeholders, and will therefore push for honest responses even more in the future at briefing stage.

Both Ghazwa Alwani-Starr and Jane Harrington absolutely supported the notion of a formal building custodian function, highlighting that it need not be a dedicated role. However, as Jane says:

You do need it to be part of somebody’s ongoing remit, and ensure that the vision is never lost as people change jobs.

Balancing openness and privacy

The balance between privacy and openness emerged as an important issue for building users. At the Bristol Business School, users confirmed that the building inspired a sense of wonder and had a ‘wow’ effect, and they were proud of its welcoming transparency. As well as enjoying views across the atrium and to the outside, it’s clear that users took ‘voyeuristic’ pleasure at being able to see staff and students at work through all the glass walls. Interestingly, these were often the same people who wished for more privacy themselves.

From the inside looking out, the lack of privacy caused some discomfort, leading to feelings of ‘being in a goldfish bowl’. One memorable photo showed how occupants had taken matters into their own hands by fixing their own DIY blind across glazing using sheets of flipchart paper.

According to Jane Harrington, the extent of control that users should have over their environment is a balancing act that varies with different segments of the user group. In contrast to the reaction of the UWE staff, she cites the example of University of Greenwich staff at the Stockwell Street building: “They are a group of predominantly arts-based staff, and they tell me that they like open-plan. They see it as a way of developing their academic subjects together.”

Ghazwa Alwani-Starr agrees that it is about striking a balance, using contemporary design standards when moving away from the long, forbidding, windowless corridors of older university premises. For her, transparency is multi-layered and must respect the diversity of needs, not just from person to person but at different times of the day and week as people cycle from concentrated private work to collaborative group work and back again.

She has empathy for students giving talks to their peers in glazed rooms. “To be watched by people not engaged in your activity – standing outside pulling faces, perhaps – is intimidating. Uncontrolled and unmanaged interference with what you are doing creates anxiety.”

Matt Tarling acknowledged the challenge of getting it right:

Trying to get one size that fits all users is incredibly difficult. It’s about flexibility that allows people to adapt as and when they need.

The research project is summarised in an illuminating report, freely available here. It includes a briefing toolkit that Stride Treglown is already using to improve outcomes for our university clients. If you’d like to know more, please get in touch with Cora Kwiatkowski.